(Here’s the sermon I offered at Grandview United Methodist Church in Lancaster, PA on Sunday, April 2, 2017 on the subject of trauma, shame and healing. There’s an audio recording of it here)

One of my personal heroes, Father Greg Boyle, of Homeboy Industries has said,

But it occurs to me that to achieve a real sense of KINSHIP with those who are marginalized requires a deep understanding and acceptance of our own imperfections and brokenness or, as one of Father Greg’s “homies,” former gang member Jose, says,

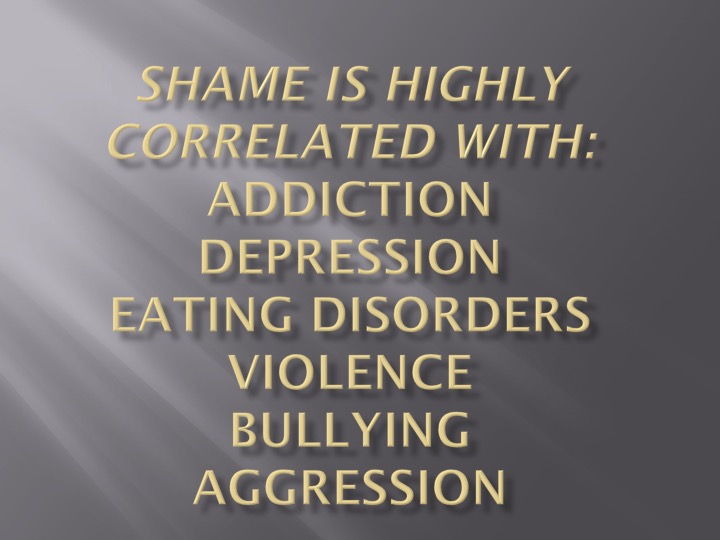

My work as Director of the RMO, a prisoner reentry initiative, is with people who carry numerous wounds: addiction, mental illness, poverty, violence, the dehumanization and stripping of dignity that goes with incarceration, not to mention the additional wounds of shame, stigma, and being judged, labeled and ostracized by the community as “criminals”, “offenders”, “ex-cons”.

For longer than I’d like to admit, I had been operating under the delusion that to serve them effectively, I needed to be a pillar of strength and model of someone who had things pretty well figured out.

The core messages of my childhood were:

and

Those messages steeped me in what author and shame researcher Brene Brown calls the “myth of self sufficiency.” In her book, “The Gifts of Imperfection”, Brown writes,

I finally came to understand that in my work, I was often attaching judgment to “helping” people coming out of prison because I had not come to a full understanding of my own brokenness and my own need for help. And I had to make the painful admission that the reason I had not done so was SHAME.

Some of my shame comes from having grown up with a mother who struggled with addiction and, later, mental health issues, and the pain and trauma that created for me throughout my life. And because I had not done the necessary inner work to transform my pain, I transmitted it to others around me by being judgmental and critical, with a “holier-than-thou” arrogance. I hurt people because I was hurting.

Those childhood messages: “Don’t air your dirty laundry” and “Pull yourself up by your own bootstraps” meant that, for years, I didn’t recognize or acknowledge, and certainly didn’t talk about, any of this. When I was a kid, our family did go to church regularly on Sunday mornings, all cleaned up and dressed in our finest. But even at church – in fact, I now think, ESPECIALLY at church – we kept silent about what was going on with my Mom’s addiction behind the closed doors of our home.

This morning, there are many people, many families, in many churches, in many places – even right here in this place – who are sitting in silent shame, over things going on in our lives, how we feel about ourselves and the kind of people we are, about sinful and shameful things we have done that have hurt others or ourselves, about things our loved ones have done. And there are many additional people who feel such deep shame that they feel like they aren’t even worthy to come into a church.

(This is the “squirmy part of this sermon” . . . but that’s okay . . . stay with me here . . . )

Brene Brown says that shame needs three things to grow exponentially in our lives:

Her research shows that:

In other words . . .

We are afraid to admit or let anyone see the broken places in our lives. We may think, “If others knew this about me, would they still accept and love me?”

But here’s the good news: There IS a way for us to overcome those fears and address our shame, so we can heal and move forward.

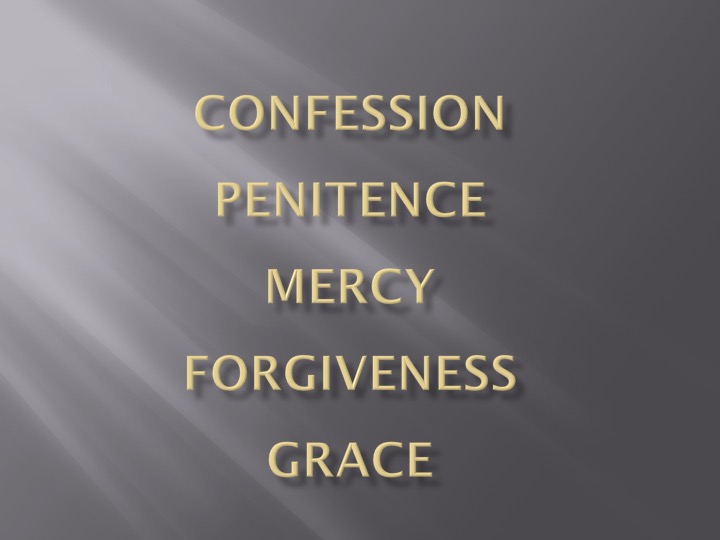

The scientific research shows that the best way to address shame is to bravely bring it out into the light of day, to acknowledge what’s broken in our lives, to name it, TALK about it with trusted others who will offer us compassionate listening, empathy, and forgiveness and to ASK FOR HELP.

We can’t do it alone. Here’s the secret: There’s NO SUCH THING as pulling yourself up by your own bootstraps. It’s a myth. We need each other.

Interestingly, what the research shows will help us deal with our shame are the same things that our Christian tradition teaches us: the things we know as:

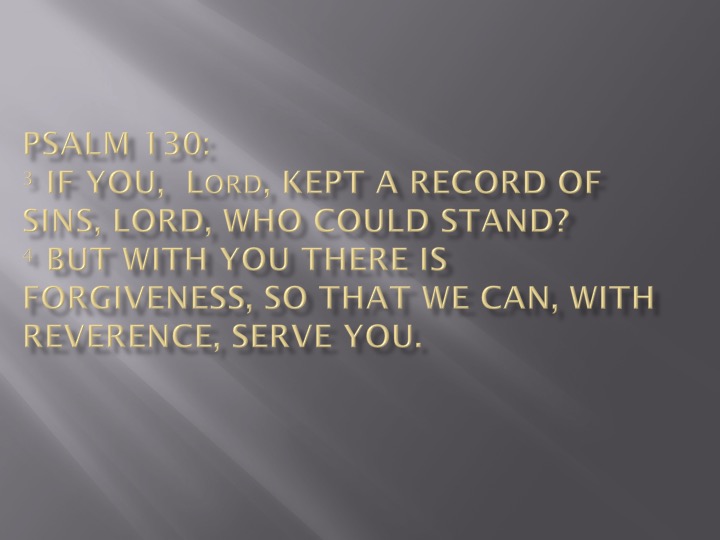

Pastor Andrea said in the first of her sermons in this series that the CHURCH has a vital role to play in healing shame and creating healthy community, because of the church’s unique offering of GRACE: the central tenet of our faith as Christians and the focus of this morning’s lectionary texts.

and in the passage from Romans:

These promises of God’s grace and forgiveness, of God’s abundant love, despite our sinfulness, our brokenness, are what give us HOPE. God’s abundant love is so much stronger than our fear of admitting to the brokenness in our lives.

Another of my personal heroes, Bryan Stevenson, author of the book Just Mercy, writes,

One of the things I’ve learned through my work with the RMO is that there’s pretty extensive evidence that a majority of the people in our prisons and jails have had a history of trauma in their lives – often when they were children. They’ve experienced emotional, physical and sexual abuse, emotional and physical neglect. Many have grown up in households with a parent who had addictions or mental illness. Many have witnessed domestic violence and other forms of violence. Many have lost a parent to death, abandonment, or incarceration.

It isn’t that these experiences excuse what they have done to harm others, and we may struggle to feel compassion for THEIR PAIN, asking what about the pain THEY have caused?

And that’s absolutely a fair question, with, I admit, no simple answers. And yet, our common humanity and our Christian teaching compel us to recognize THEIR SACRED WORTH rather than judging and shaming them; to EMBRACE them; to truly LOVE them as our NEIGHBORS.

I like what the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow once wrote:

Much of what we do with brokenness in our own lives, as well as the lives of people with addictions, mental illness, and those in our criminal justice system, is like using an aspirin and an ice pack for a broken leg. While aspirin and an ice pack might temporarily relieve the pain and reduce the swelling, the TRUTH is that the leg is still broken – and if we never PROPERLY mend what’s broken inside of us, it may continue to “cripple” us.

But I’d like to close this morning by offering a different vision for mending the broken places in all of our lives.

In Japanese culture, beautiful pottery is an important part of everyday life – pottery bowls, plates, cups and vases.

When a bowl or vase or cup or plate gets chipped, or cracked . . .

or even completely broken into pieces . . .

rather than throw it away, they have a beautiful traditional practice called:

or as it’s sometimes called, “mending with gold.”

What they do is mix up a lacquer to which they ADD precious metals – usually GOLD DUST –

Then they take the broken pieces of that bowl or vase or plate, and they carefully and lovingly apply the golden lacquer along the broken edges and join the pieces back together.

Their philosophy is that when something happens that damages a piece of pottery, it should NOT be tossed aside or thrown away as worthless. Instead it is WORTH taking the time and care to mend what’s broken.

They treat the breakage and the process of repairing it as simply part of the history of that object, instead of something to be hidden or disguised.

They believe that chips, cracks, even completely breaking into pieces – these are all just natural parts of life.

Not only is there no attempt to hide the cracks and brokenness, but the repair is literally illuminated.

And because they have used precious metals (GOLD DUST!) . . .

to mend the broken places . . .

. . . the resulting piece is considered even more valuable and beautiful than the original.

We are not called to be perfect. We ARE called to be light and love to one another. Acknowledging the cracks in our own lives, and letting the light get in, can help us to heal our own brokenness, and give us the capacity to be compassionate, wounded healers in kinship with others.

Here’s what the research says about what we need to HEAL from the trauma of our own inner brokenness: We need:

Here’s what the research says about what we need to HEAL from the trauma of our own inner brokenness: We need:

- Opportunities to share our stories with empathetic listeners

- Meaningful connection with others

- Support from trusted others

- Spiritual connections: a sense of something larger than ourselves

- Opportunities to participate in social activities

- Opportunities to be of service to others

- Healthy, meaningful rituals

- Opportunities for fun, play, laughter

- Opportunities for creative endeavors

- Opportunities to connect with nature

Amazingly, the CHURCH offers EVERY ONE of these things – and all of these things foster the kind of KINSHIP that Father Greg Boyle talks about.

In Jane’s Dutton’s sermon a couple of weeks ago – she highlighted the repetition in New Testament stories of the words: “Us”, “Our” and “We” – this is the language of KINSHIP. And I love that the word “Kintsugi” is so similar to “Kinship.”

Grace is like that lacquer mixed with gold dust – God’s grace can mend the broken places in ALL of our lives, making us whole again, even more valuable and beautiful than before.

And through our compassion, love, empathy, and golden offerings of grace to others, we can be instruments of God’s ultimate transformation, to make gentle a bruised and broken world.

SO, I echo Pastor Andrea’s call to all of us in her first sermon in this series: to live into who God created us to be – wholehearted people who make up a grace-filled AND grace-giving body called the CHURCH.

Mending the chipped and cracked and broken places in our own and one another’s lives with God’s golden, and amazing grace.

Today would have been my Mom’s 76th birthday. Mom died eight months ago after a 50+ year battle with the grave disease of addiction and, in her later years, significant mental health issues.

Today would have been my Mom’s 76th birthday. Mom died eight months ago after a 50+ year battle with the grave disease of addiction and, in her later years, significant mental health issues. But the good news is that research also shows that the best way to address shame and to build resilience is to bravely bring these difficult subjects out into the light of day, to acknowledge what’s broken in our lives, to name it, talk about it with trusted others who will offer us compassionate listening, empathy, and grace, and to ASK FOR HELP.

But the good news is that research also shows that the best way to address shame and to build resilience is to bravely bring these difficult subjects out into the light of day, to acknowledge what’s broken in our lives, to name it, talk about it with trusted others who will offer us compassionate listening, empathy, and grace, and to ASK FOR HELP. One of the things Mom and I shared in common was a great love of traveling to new places. So, I took Mom with me on this three-week trip, sprinkling her ashes in each of the trauma-informed communities I visited. Leaving a little piece of her, and by extension, a little of myself, in communities that have committed themselves to healing, strength, resilience, and grace seemed like a fitting tribute to her life.

One of the things Mom and I shared in common was a great love of traveling to new places. So, I took Mom with me on this three-week trip, sprinkling her ashes in each of the trauma-informed communities I visited. Leaving a little piece of her, and by extension, a little of myself, in communities that have committed themselves to healing, strength, resilience, and grace seemed like a fitting tribute to her life.

Here’s what the research says about what we need to HEAL from the trauma of our own inner brokenness: We need:

Here’s what the research says about what we need to HEAL from the trauma of our own inner brokenness: We need: